Monday, October 14, 2013

The Stigmata of Mother Earth

After the 1986 meltdown and explosion at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in the Soviet Union, a massive effort was made to evacuate the area which was receiving the heaviest doses of radiation. A hundred thousand people were hastily removed, and whole cities were abandoned. The 2600-square-kilometer Chernobyl Exclusion Zone was established, and today access to this region is heavily restricted. Parts of it remain highly radioactive.

Images from the zone are eerie. Children's toys are abandoned in an evacuated kindergarten. The reactor control room is filled with corroded consoles full of shattered instrument dials. Bumper cars rust in an amusement park. A lonely statue of Lenin presides over an overgrown park. It is like those "Life after People" television documentaries.

There are signs, though, of reinvigorated nature. Forests are flourishing, and many wild animals now roam the abandoned cities. Maybe, we might think, there is hope that this area, so damaged by human activity, might eventually return to a natural state. Maybe this region will heal itself in the long run. Maybe it will be OK.

There are scars that will not heal easily. Plants and animals show odd mutations. Pine trees have a peculiar red color to their bark caused by radiation. Birds grow assymetric wing feathers and are unable to fly. Some insects have become extinct. Grass and forest fires spread new blasts of fallout into the atmosphere. The harm done by humankind is still present, and will be for many generations to come. We can see and touch the scars left by human carelessness.

Still, there is hope for the future in the plants and animals that live in this ruined landscape. Wolves, bears, wild horses are found for the first time in generations. Plants find ways to flourish and grow.

The Gospel according to John describes the Risen Christ in strange terms--he seems mysteriously unknown to his closest friends. His body still bears the marks of the murderous torture that killed him, yet he speaks, eats, drinks. He is the same, he is a "normal" human, yet he lives with the signs of what killed him.

I'd like to suggest that the Earth herself bears the scars of what we humans have done to her, yet lives on, not unlike the Johannine image of the resurrected Jesus. Just as the living Christ can show his friends the wounds he has suffered, yet is alive among them. so we can see the scars of what humanity has inflicted on the Earth.

It is not only Chernobyl, of course. We can also look at the wounds of rising sea levels, pollution of air and water, habitat destruction around the globe.

And yet Mother Earth lives, and offers us her promise for the future, despite her signs of our careless selfishness. Just as we of the Body of Christ cherish the One Who Lives among us, just as we see hope in him, just as we rejoice in his transcendent love and presence, so may we care for our Mother the Earth, and do what we can to aid her rebirth, even as we look on the wounds we have inflicted on her.

Wednesday, September 18, 2013

Who Does God Trust?

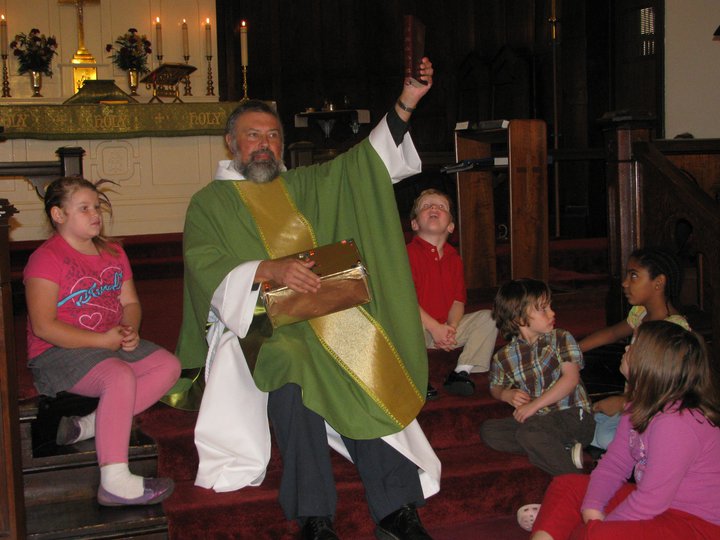

Once a month, I offer an alternative service in my church parish hall aimed at our young children. Last Sunday, we focused on Jesus' parable of the Lost Coin. I had ten quarters. Nine of them were at the "altar" (a parish hall table in this service) and one was hidden in the room. It didn't take long for my young detectives to find it. When they did, I underlined the point--if you do bad things, God loves you enough to be happy when God has you back.

Brandon, a ten-year-old theologian, posed an interesting point: "If you do bad things too much, God won't trust you anymore."

Does God trust us? The anthropomorphized God of the Bible has good reason NOT to.

"OK, you two: I'm giving you every single thing you need to be completely happy. Just don't touch this one tree I'm putting here in the middle of the garden. Remember, I'm trusting you!"

"David, I'm raising you up as king over Israel, and I expect you to be wise and just. So don't do anything stupid, like killing somebody so you can steal his wife. I'm trusting you here!"

"I'm sending my beloved Son to live as one you. I expect you to listen to him, follow him, and honor him as the Messiah. I hope I can trust you."

"I'm boiling down all those commandments into just two: love me, love other people like you love yourself. That's pretty simple, isn't it? I'll trust you to do those two simple things."

I don't know about you, but I think God would be crazy to trust us humans. But can God love us, even if we aren't very trustworthy? I hope so.

We human beings seem to find ways of putting ourselves and our wants and desires first. We can always rationalize doing what WE want to do. With the possible exception of a few great saints (and I kind of wonder about them, to be honest), we haven't done a very good job of earning God's trust.

So, my friend Brandon, you're right. God has good reason not to trust us, because we do bad things. It's a good thing God loves us. We don't have to earn that.

Does God trust us? The anthropomorphized God of the Bible has good reason NOT to.

"OK, you two: I'm giving you every single thing you need to be completely happy. Just don't touch this one tree I'm putting here in the middle of the garden. Remember, I'm trusting you!"

"David, I'm raising you up as king over Israel, and I expect you to be wise and just. So don't do anything stupid, like killing somebody so you can steal his wife. I'm trusting you here!"

"I'm sending my beloved Son to live as one you. I expect you to listen to him, follow him, and honor him as the Messiah. I hope I can trust you."

"I'm boiling down all those commandments into just two: love me, love other people like you love yourself. That's pretty simple, isn't it? I'll trust you to do those two simple things."

I don't know about you, but I think God would be crazy to trust us humans. But can God love us, even if we aren't very trustworthy? I hope so.

We human beings seem to find ways of putting ourselves and our wants and desires first. We can always rationalize doing what WE want to do. With the possible exception of a few great saints (and I kind of wonder about them, to be honest), we haven't done a very good job of earning God's trust.

So, my friend Brandon, you're right. God has good reason not to trust us, because we do bad things. It's a good thing God loves us. We don't have to earn that.

Wednesday, August 28, 2013

Light and Smoke

What if there was a holy place where people of all ages came

and went as they pleased? What if they offered prayers entirely on their own,

in whatever words (or non-words) they chose? What if there were no clergy or

religious leaders to give people permission to pray, or to make sure they were

doing it right?

I am fortunate enough to have been to such a place. It has

the lovely name of “The Palace of Peace and Harmony Lama Temple.” It was once a

residence of the Qing Dynasty prince Yinzhen. After he took the throne as the

Yongzheng Emperor in 1722, he gave this property to the colony of Tibetan monks

who lived in Beijing. I spent a morning among the clouds of incense—and prayer—during

a recent trip to China.

I came to China with a preconception. I assumed that modern,

post-Mao China was non-religious, if not anti-religious. I was aware that

several faiths were practiced under the watchful eye of the government in a

nation that is officially atheist. I was expecting the Lama Temple to be more

museum than active place of worship.

My first surprise: as I walked from a nearby subway station

to the gate of the Temple, the sidewalk was crowded with energetic salespeople

hawking incense sticks. After having the long, cellophane-wrapped packages

shoved in my face by importunate sellers a few times, I decided to buy a

package, if only to show that I was not, thank you very much, interested in

buying more.

The gate of the Temple gives into a peaceful avenue lined

with willow trees. There are five main halls, each with one or more statues of

the Buddha. Before each building stands an oil lamp used to light the incense

sticks. A kneeling bench that would not look out of place in an Episcopal

church faces the hall. Most people would light three sticks of incense and

kneel with the smoking sticks held up to their foreheads. After a few minutes,

they would rise and bow to the four cardinal directions. The incense would be

left in a bronze brazier, where it would continue to smolder along with the

sticks left by other worshipers.

So, what was I, a Christian, going to do in this place? I

did not want to simply imitate the practices of a faith that was not my own. As

I looked upon the serene face of the Buddha, those first couple of commandments

were in the back of my mind also. (You know—the ones about “no other gods

before me” and “graven images.”) Since one of my many heresies is panentheism,

the belief that God is present in all things, I decided that I could add my own

devotions to those of the many who were with me.

My ritual created on the spot: I lit my three sticks of

incense and prayed for enlightenment, a proper sentiment, I thought, which

would be approved both by the former Indian prince and the carpenter-rabbi of

Nazareth. I made a discreet sign of the Cross with my incense, and then added

it to the other sticks smoldering in the bronze urn. My prayers, along with

those of many others, would continue to rise in the fragrant smoke.

Is there a holy place like this in culturally-Christian

America? When did you last see working people, teenagers, and elderly folk

praying on their own, without someone supervising their practices, or

instructing them from on high? There were a few monks among the crowds, but

they seemed to be offering the same devotions as the “civilians.”

I’d like to think that I brought home a little of the Palace

of Peace and Harmony Lama Temple. I will strive for times of mindfulness and

enlightenment as I go about my daily life. I hope my prayers continue to rise,

even when I go about my life.

Thursday, August 22, 2013

Repairing the Shattered World

The sixteenth-century Jewish mystic Isaac Luria offered an interesting explanation of the mess the world is in. God, said Luria, created the world by placing his own divine light into vessels. These containers could not hold the powerful essence of God, and shattered into shards. The calling and duty of religious folk is tikkun ha-olam, the "repair of the world." By ritual acts and by living day to day according to God's commandments, the broken is brought together, the shattered is made whole. In this way, the world is made into a place that is worthy of the Messiah who is to come.

Although Christians and Jews might disagree about whether the Messiah is coming for the first or second time, I as a Christian find the call to tikkun ha-olam a much more compelling notion than the idea of waiting passively for the Lord to arrive, cause the rapture, initiate the war of Armageddon, etc., etc. For centuries, Christians have scanned the news of the day and searched for events that seem to be congruent with the fierce and cryptic poetry of the Book of Revelation. By this reading, the End Times never quite seem to get here, and it's back to the drawing board to interpret the signs of the times.

While others dissect apocalyptic literature, I am going to do what I can to practice tikkun ha-olam. I see the hungry every day, and I do my best to feed them. I serve in an organization in my community that provides shelter to children in state custody, counseling to the addicted, and care for the victims of domestic violence. I know my local political leaders and leaders of city government, and I don't hesitate to discuss my concerns about how to make a better community with them.

In classical theological terms, this makes me a "post-millennialist." I'm not waiting around for the Messiah to show up to fix the world. I'm doing my small part to assemble the shards that come before me.

Can you find opportunities to practice tikkun ha-olam in your patch of the world? What can you and I do to make the world more just, more decent? How can we be better stewards of the gifts of nature? How can we put the pieces together and make better vessels where we live and work?

The picture that heads this post is an example of the Japanese art of kintsugi, or "golden joinery." When a precious vessel is broken, it is repaired using a lacquer made with powdered gold. The cracks gleam with the beauty of the artist's hand, and show that care and love have gone into the repair. Let's use the same love and care in repairing the broken world.

Monday, August 19, 2013

The Mystery Box

Every

Sunday, I am challenged during our worship service by. . . the Mystery Box!

Each Sunday,

one of the kids in our church family takes

home a box, grandly spray-painted in gold and covered with “precious jewels.” That

child is invited to put anything he or she likes, with the exception of living

organisms, into the box and bring it back to church the following Sunday. During the service, I open the box to see

what’s in it. And then I have to say

something useful and memorable about the box’s contents, and connect it in some

way to the Bible, Christian faith and practice, or generally to the things of

God. This game is also sometimes called

“Stump the Preacher.”

Quick! Say something biblically relevant about this

Transformer toy, bag of Gummi Bears, stuffed hippopotamus, naked Barbie doll. It’s a closed book test—no time to consult

the Bible, the works of St. Augustine, or even call the bishop for guidance.

Of course,

this happens to all of us, all the time, doesn’t it? Every day, we are faced with unexpected

challenges that call on us to reach down to the roots of our faith. We make the decisions that are set before us

by daily life, using the best judgment we have, and the light that God gives us

for guidance.

What should

I do? The doctor tells me I have a

serious heart condition. My son was just

arrested. I just had a terrible argument

with my spouse. We could all add a

million examples to the sudden, unexpected turns that our lives might

take. Over and over, we are handed a

Mystery Box, and we have to figure out how to react.

We may not

always have the Bible or authoritative sources to consult, or someone to advise

us. What each of us do have is a lifetime of experience to draw on, and the moral and

ethical instincts within us. There is,

to be sure, a human tendency in all of us to put our own will and desire before

the will of God.

But there is

also within us, even if we don’t always listen to it, a sense of what is right

and what isn’t. This is also molded from

what we have been taught, the example of parents and others, and our religious

traditions. Christians call this the

Holy Spirit within us, that guides and rules our actions. It is this Holy Spirit that teaches us what

to do with the Mystery Boxes that life sets before us.

With God’s

loving presence in our lives, we should never be afraid to open the Mystery

Box.

Wednesday, August 14, 2013

Heaven? Neurotransmitter Secretion?

We've all heard the stories. Someone in cardiac arrest experiences the sensation of leaving the body, of moving toward a bright light. Often there is a powerful sense of another personality, otherworldly and seemingly divine. Powerful emotions are often part of this experience. Eventually, there is a return to the world of the ordinary, with a sense that a profoundly important and life-changing event has happened, one that will shape the rest of the life of the person who has been through it. Neurosurgeon Eben Alexander had such an experience, and he considered it "proof of heaven." His book with this title has been on the New York Times bestseller list for 41 weeks.

Newly published research suggest a physiological explanation for these phenomena. Studies in rats show a spike in electrical activity in the oxygen-deprived brain. Researcher George A. Mashour told the Washington Post, “We

saw a window of activity with certain signatures typically associated with

conscious processing.”

So, which is it? Being in God's presence, or the firing of neurons in an oxygen-depleted brain?Those signatures include heightened communication among the different parts of the brain, actively seen in an awake state. Mashour speculates this could be a marker of consciousness — in which the brain integrates disparate aspects of the world, like visual in one area and auditory in another.“The brain kind of gets it all together so we have this unified, seamless experience,” he said.In the rats, this connectivity went above and beyond the levels seen during the awake state — which could possibly explain the hypervivid, “realer-than-real” perceptions reported close to death.

Does it matter? Profound spiritual experiences are often rooted in the events of the real and physical world. What makes an experience spiritual is how we understand and process it, much more than what we actually live through. You and I might be standing next to each other on a hilltop, watching the sun rise. You may be thinking, "This is important. This is a truly New Day. There will be significant, beautiful things that will come of this sunrise." I, on the other hand, may be thinking, "Hmm. Must be about 6 AM." We had the same experience, but processed it differently.

I don't doubt that Eben Alexander truly believes that he had "proof of heaven" and that he had "journeyed into the afterlife." This is true for him, and has changed how he views himself, the world, and God. That the first step of his entry into the dimension of the divine may have been the firing of neurons in his brain does not reduce the importance of the experience.

The matter and phenomena of the physical world are all potentially sacramental--simple things that carry God's grace. We only need eyes to see them.

Sunday, August 11, 2013

Little Church, Big Church

I am at my church at one of my favorite times of the week: early on Sunday morning, with no one around. Early light filters through the quiet from the stained glass windows. Birds outside, passing cars, the murmur of an air conditioner are all you can hear.

The church has been made ready for our celebration of Christ's presence. Bread and wine are prepared, to be ceremoniously placed on God's table. Polished silver and spotless linen rest under silk brocade. Candlesticks are placed just so.

We Episcopalians are all about reverent preparation for worship, and care in carrying it out. We concern ourselves with niceties about the exact position of creases on ironed linens, the order in which candles are lit or extinguished, the precise moments at which the Sign of the Cross must be made.

I'm calling this precisionism about worship "Little Church." Not "little" because it is insignificant, or even because our church building is of modest size. It is "little" because it is contained, of manageable size and duration. We know worship takes about an hour, and we know the order and most of the words we will say and sing. This weekly encounter with the uncontainable majesty of God allows us to think for a few moments about who we are as God's children, and what God wants us to be.

"Little Church" is really preparation for "Big Church:" the great world outside the walls of the church building where we find ourselves day to day. It is not ordered and neat like "Little Church." It is a messy chaos of emotion, politics, hard decisions, encounters with injustice and suffering.

"Big Church" is God's House as much, if not more, than "Little Church." God dwells in the broken and suffering neighbor, in the challenges of living in community, in the decisions we make about how we use our time, our money, our bodies, our minds.

I performed many acts of worship in "Big Church" this week. I paid a water bill. I shared coffee with friends. I brooded about the actions of my elected representatives. I saw a stage performance about personal growth, love, and self-awareness. I discussed the meaning of scripture passages about same-sex relationships. Amen.

Later this morning, I will tell my congregation to "go in peace to love and serve the Lord." That's when the worship at "Big Church" begins.

Thursday, August 8, 2013

God's Technology

I’d like to inaugurate the new website for Trinity Episcopal Church, and this new blog, with some reflection on technology and religious communication.

If you visit the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum in

Jerusalem, you will see a twenty-four-foot long parchment scroll with the entire

book of Isaiah. It was produced by scribes around 150 BC who copied from

earlier manuscripts. This process had been repeated in the several centuries

since the book of Isaiah took its final form around 500 BC.

This was advanced communication technology for the time:

carefully scraped sheep hides, ink made from the soot from olive oil lamps,

honey, vinegar, olive oil, water, and gall; pens hand-cut from reeds. That was

as high-tech as it got for many centuries.

When printing presses with movable type came into use in

Europe in the fifteenth century, among the first major works to be printed was

the Bible. A century later, the Book of Common Prayer was set in type for the

use of the congregations of the Church of England.

Inexpensive printing, mass magazines, radio and television,

the internet, social media, cell phones and texting, YouTube. . . whew! All in

the name of connecting our lives with the holy, and with each other in our

spiritual journeys.

I am always the last guy to adopt new communications

technologies. I managed without a cell phone for a long time, fairly happily. Also, my computer with the 8086 processor was

all I needed forever. Cable TV? What’s that? Oh yes, that thing in the box on

top of my VCR.

So. . . here we are, you and I, with this lovely new website

for Trinity Church. May we find ways to know each other, bless each other, and

open our hearts and our lives to the presence of the God of All, and our

brother Jesus. And may we learn new ways from each other to serve as Christ’s hand

and heart in this world.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)