He called me

out of the blue yesterday afternoon.

“Father Tom”

(not his real name), an 86-year-old retired priest who once served in my

Episcopal Diocese of Oklahoma, has been in California for almost forty years. In

a newsletter for retired clergy, he had seen an obituary for an old friend, a

retired priest whose funeral had been held at my church a couple of months ago.

Father Tom had lost track over the years, and he wanted a phone number so he

could call the widow and express his condolences.

It was, I

suppose, a lazy afternoon for both of us. We talked for an hour or so. He asked

after a number of older clergy he had known back in the day. I knew a bit about

the area of California where he lived, having numerous in-laws who live within

a few miles of San Francisco Bay. I asked him if it had been a culture shock

for him, moving from Oklahoma in the 1970s.

“One thing

was very different for me,” Father Tom told me. Since I’ve been here in

California, I’ve been out.”

Out? For a

moment, I wasn’t following him. “People here are a lot more comfortable with

gay and lesbian folk. Even clergy. It was a lot different when I was in

Oklahoma, back in the day.”

Father Tom

said that he had been aware of being gay back to his childhood. In his time, it

was something to be hidden, to be ashamed of. He had no one to talk to about

who he was, about his feelings. There were no positive role models. All he knew

were jokes and dismissive remarks about “queers,” whispers about Hollywood

celebrities, government officials exposed, shamed, and fired.

His vocation

to the priesthood came to him at the age of 16. As was common and necessary for

his time, he did his best to conceal his true self if he wanted to be a priest.

After college, he went to seminary, an all-male experience in his day in 1949.

He was aware of other seminarians who were partnered, and others who discretely

visited gay bars. Because of his passion for his calling to be a priest, he

lived a celibate life, and did his best to overcome his own nature.

He dreaded

the canonically required psychological evaluation. A sympathetic psychiatrist,

himself gay, certified Tom as fully heterosexual, and opened the way to his

ordination. Father Tom believes that the Episcopal bishop of Oklahoma in the

early 1950s, a gentle and kindly man, knew or suspected his orientation.

Nothing was ever said. In his years in ministry in Oklahoma, he served

faithfully and well. Over the years, he heard many jokes and remarks about “fags”

and “fairies” from many people, including, sometimes, his fellow clergy.

Slowly, he

found a support system of other closeted clergy. Eventually, he found a

partner, and had to live a life of caution and deception, always being careful

of revealing too much of who he was to the wrong person.

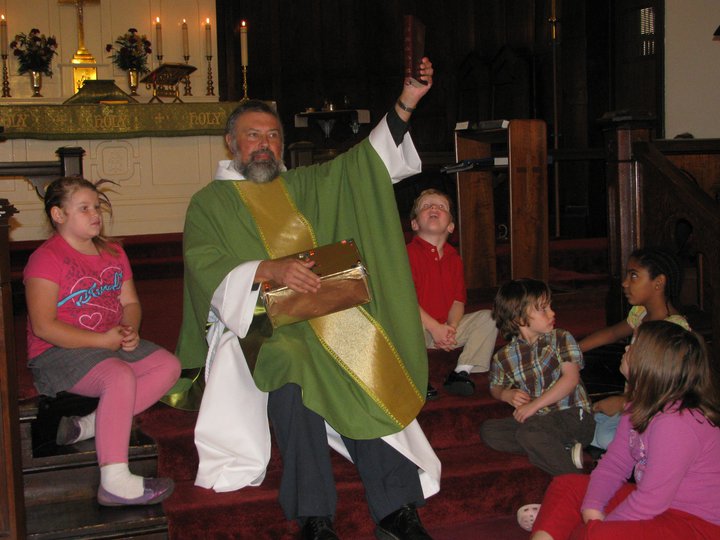

Father Tom

is long since retired from full-time ministry. Today, he is vigorous and active

in his priesthood, celebrating the sacraments regularly at retirement

communities and supplying in parishes.

We talked

about how the Church and the world had changed in his 62 years as a priest. He

had kind things to say about my modest efforts to welcome LGBTQ people to my

congregation, including being able to offer the blessing of same-sex unions in

compliance with the policies of my diocese, and joining with other local clergy

to offer a series of discussion forums on the Church and the gay-bi-trans

communities.

I was

blessed by this conversation. The flame of priesthood still burns brightly in

this old man, who speaks openly, even cheerfully, about his long and sometimes

difficult journey. God love you, Father Tom, for your courage and strength in

being who you are. I am honored to share the calling of priest with you.